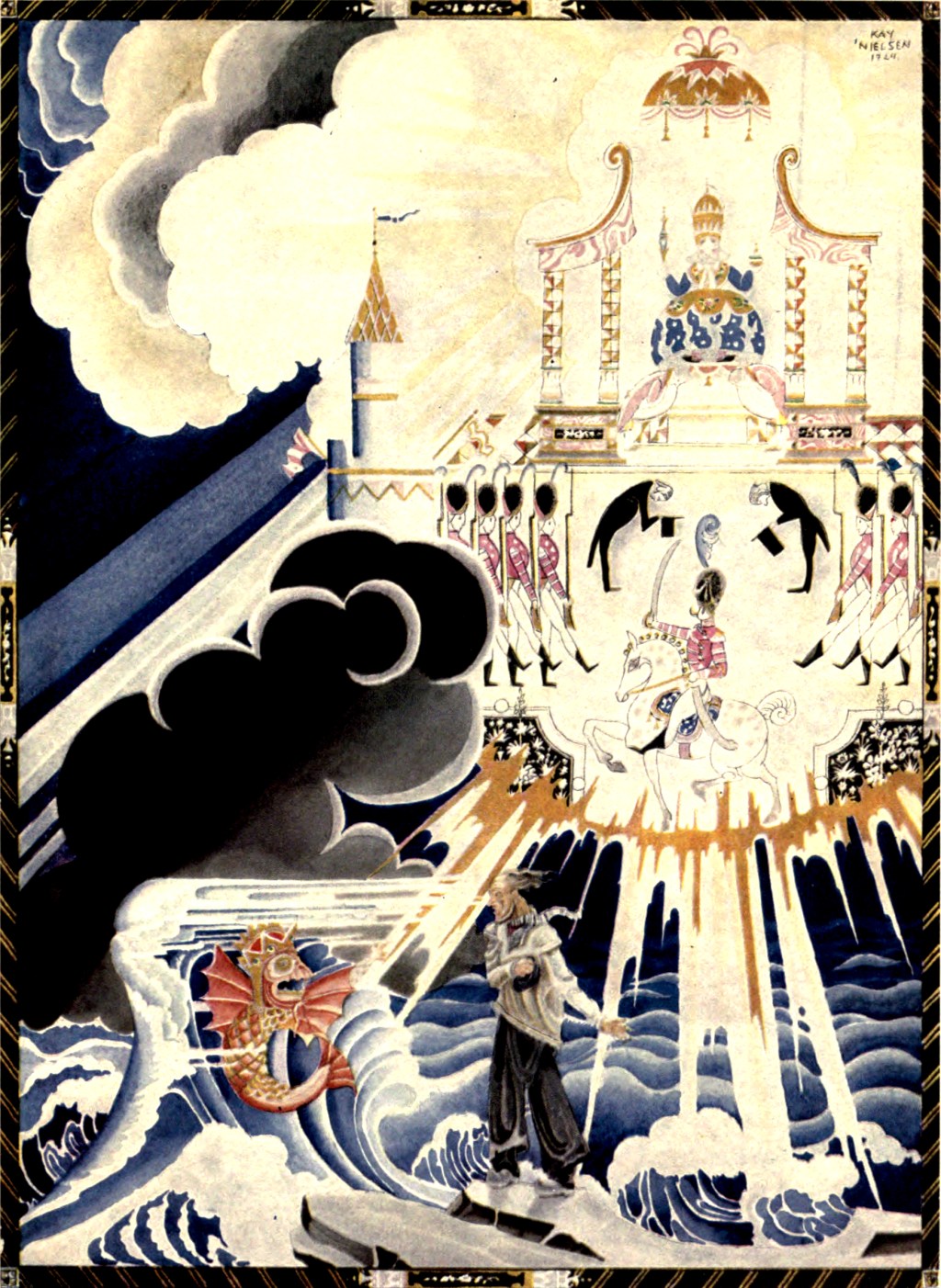

If you feel adventurous this Christmas, I encourage you to read a fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm called The Fisherman and His Wife.

My contention is that this Low German fairy tale presents the true meaning of Christmas far better than Buddy the Elf, The Grinch, George Bailey, Ebenezer Scrooge, and maybe even Charlie Brown (maybe).

I am not going to summarize the story here because I really do want you to read it. It’s a fairy tale for children, it’s not all that long and it might even do you some good. Seriously, just read it.

If you have read it, you might be wondering what it could possibly have to do with Christmas, or maybe you’re already starting to piece it together. Either way, like the fisherman looking into the clear sea water, let’s look together into the deep simplicity of a fairy tale.

Based on many of the various adaptations and interpretations of this tale that I’ve come across, it seems like most people see the end of the story as a simple irony resulting in a moral caution against greed and an encouragement to be content with what you have. Here are a handful of explanations I’ve found online:

“

Eventually everyone learns that you must be careful what you wish for if you want to hang on to what’s really important.1

“

The real lesson is to simply appreciate what you have. You should always be doing what you can to make your life fulfilling and rewarding, but don’t expect possessions and fancy titles to make you happy. ‘Cause if that’s all you’re pursuing, then you’re always gonna want more.2

“

This story teaches about gratitude, greed, and being satisfied with what we have. Ask your child: “Why did the wife keep wanting more?” and “What happened because she wasn’t grateful?” The tale helps children understand that constantly wanting more can lead to losing what we already have, and that happiness comes from appreciating our blessings. Ideal for ages 6-10!3

However, I don’t find any of these explanations very compelling, mainly because they are not narratively coherent, nor are they necessarily true.

In the first place, it is not always true that “wanting more can lead to losing what we already have” (unless you are playing Blackjack or Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, I guess). Oftentimes greed is rewarded right up to the end—albeit accompanied by a certain moral bankruptcy, as we often see in more modern fairy tales like Citizen Kane.

And in the second place, the “be careful what you wish for” motif typically boils down to unintended consequences or unread fine print. This usually involves some kind of gotcha in the fulfillment or some negative element inherent to the wish which is overlooked by the wisher in the heat of the moment (q.v. The Monkey’s Paw—conditional wishing, or, in keeping with the Christmas spirit, the unintended consequence of a wish in Home Alone or It’s a Wonderful Life).

But here, each wish is fulfilled with no explicit conditions or unintended consequences whatever. In other words, narratively speaking, there is no indication that the wife overstepped a boundary of some sort in her final wish, or that the flounder played a puckish trick on her, or passed any kind of cosmic judgement sentence based on her boundless avarice.

All he says is:

“

“Go to her, and you will find her back again in the dirty pigsty.”

But then, if we don’t think that the outcome of the final wish is a necessary consequence or punishment of the wish itself, we are left with a very strange thought:

What if the wife’s final wish was actually granted by the flounder?

Ah, now we see a new angle which cannot so easily be summed up as a simple cautionary tale.

Now we read the last line and it’s as if the flounder says:

Very well then. If you would be like unto God, you must content yourself to live in a dirty pigsty —

And we may add:

— even as He himself did.

In this light we find a different, deeper significance.

Instead of an exhortation to simple contentment, we find an exhortation to self-emptying.

Instead of a warning against greed and gain, we find an example of complete and total submission.

And ultimately, we find two ways to be like unto God.

The first way, is Isabel’s way. And if we listen very closely to the requests of Isabel throughout the story, we may hear the echo of another voice, one much older, who also wanted to be like unto God. We hear the echo of a temptation to power over all the kingdoms of the earth and their glory. And we hear the hissing echo of a temptation to be like unto God, on our own terms.

But in the end we find the second way to be like unto God—the flounder’s way. The true Way.

The way which willingly puts aside god-like position for the lowest estate. Because Isabel’s final request is not an unreasonable request. In fact, it is the noblest request of all. To be like God is, literally, godliness.

But in this request, to be like unto God, we really should be careful what we wish for, and we should make sure that we know what the God we wish to be like unto is really like. For it is written:

“

Though he was in the form of God, [he] did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, by taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men.

— Philippians 2:6-7

To be “born in the likeness of men” is a condition for which even we humans often enough find cause to cry out with Captain Ahab:

“

Oh God! that man should be a thing for immortal souls to sieve through!

But for God himself—who not only causes the sun and moon to rise, but is the very source and sustainer of their light and dominion in the first place—for this God to willingly condescend to be born, as man, in a dirty pigsty . . .

That is the true meaning of Christmas.

Appendix

~ ~ ~

A note on the translation

My understanding of this story is due primarily to the translation of a single word in the physical copy of Grimm’s tales that I happen to have in my possession.

Namely, the word “pigsty.”

If you did not read the version of the story which I posted on this blog, but rather found the story online or maybe dusted off your own physical copy, chances are the word used to describe the home of the fisherman is either “hovel” or “hut,” which both convey a dingy dwelling to be sure, but they have a little less figurative umph to them.

As far as I can tell, “pigsty” is the least common English translation of this word, and yet it most firmly anchors the connection to the nativity story. Even the copy that I own (the Word Cloud Classics edition) claims to be the Margaret Hunt translation (one of the oldest and most popular), however the Word Cloud version has very minor modifications from any other Hunt translation available online, but I cannot for the life of me figure out where those modifications came from. And yes, one of those modifications is the use of the word “pigsty” where Hunt’s classic translation says “hovel.”

So, not wanting to make a lengthy essay on the topic which might be founded entirely on a translation error, I did a little digging to see if I could determine whether the word “pigsty” was a proper translation from the German.

Spoilers: it is.

I had to journey all the way to the German side of Wikipedia, where you can not only find a much longer article on this story, but also the original German text of all seven editions of the Kinder- und Hausmärchen published by the Brother’s Grimm.

So, without further ado, the word used for the fisherman’s “hovel” in all seven of those German editions is the word . . . “Pispott.”

Now, you don’t exactly have to be a scholar of Low German to figure out what that word means, and, I don’t know about you, but I feel like the word “pigsty” is not only an apt translation, but probably the single best translation into English which still conveys the idea and is child-friendly to boot. Why this isn’t the most common English translation, I don’t know.

But wait. There’s more.

The German text of the Hausmärchen also includes the original academic notes added by the Brothers Grimm themselves (which was a large part of the whole project of collecting these oral tales to begin with). From these notes I also learned that my particular interpretation is not only valid, but probably intended. Here is a quote from those notes in the 3rd edition (translated by Google Translate):

“

In Hesse, [this story] is also frequently told, but in a more incomplete form and with variations. It is about the little man Domine (otherwise also called Hans Dudeldee) and his wife Dinderlinde (probably from Dinderl, meaning girl or wench?).

…

When they have wished for everything, the little man says, “Now I would like to be God and my wife the Mother of God.” Then the little fish sticks its head out and calls:“If you want to be God,

then go back into your chamber pot [Pispott]!”

Which seems pretty straightforward.

This makes me a little surprised that there is so much discussion centered around the vanilla interpretation I explained above, or otherwise far-fetched political or psychological analyses. As so often happens to these tales over time, somewhere along the way everyone has missed the original point.

So I’ve tried to explain how the story struck me the first time I read it, and also provide the translation which was the key to my understanding it that way. Hopefully it will not only give you an appreciation for this specific story, but also help you to see a little farther into the deep simplicity of other tales as well.

- The Cajun Fisherman and His Wife – Yep, like it sounds, except apparently the ultimate wish is to be Mardi Gras queen. Go figure. ↩︎

- The Messed Up Origins™ of the Fisherman and His Wife | Folklore Explained by Jon Solo on YouTube ↩︎

- AmericanLiterature.com ↩︎